Soon after Gandhi’s imprisonment, signs of a serious rift appeared among his followers. Some prominent Congressmen including Motilal Nehru and C.R. Das declared themselves in favour of lifting the boycott of the councils. They formed the Swaraj Party to contest elections to the provincial and central legislative councils and to “carry the fight into the enemy’s camp”. Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajagopalachari and others who were opposed to any change in the original non-cooperation programme came to be known as “No-Changers”. During the whole of 1923, Congress politics were extremely fluid. There were a number of resignations from the working committee and the All India Congress Committee; bona fides were questioned; ‘points of order’ were raised, and the constitutions of Congress discussed threadbare. In September 1923, at a special session of the Congress, it was decided that the Swarajists should be allowed to put up candidates at the election which were scheduled in November. The Swarajists had barely two months to fight the elections, but they succeeded in capturing a solid bloc of seats in the Central Legislative Assembly, a substantial representation in provincial legislatures and even a majority in the Central Provinces Council. Motilal Nehru led the party in the Central Assembly, while C.R. Das took up the leadership of the party in the Bengal Council.

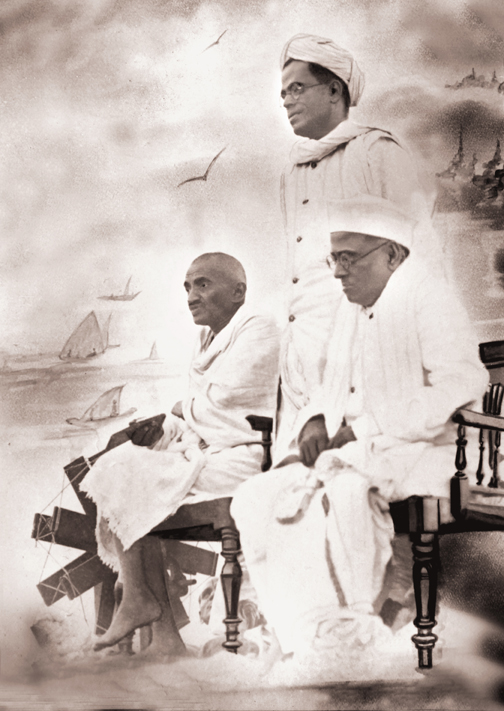

In February 1924, after he had served only two years in Jail, Gandhi, after an operation for appendicitis, was released. He did not, as his faithful No-Changers hoped, throw his weight in their favour. On the contrary, he did everything to avoid a split in the party. He made a series of gestures to the “rebels” – the Swarajists –and let them dominate the political stage. The Viceroy wrote home: “Gandhi is now attached to the tail of Das and Nehru, although they try their utmost to make him and his supporters think that he is one of the heads, if not the head.”

If the rift in the Congress ranks on Council entry was one disappointment to Gandhi, after his release from jail, the division between Hindus and Muslims was another and greater. The Hindu-Muslim unity of the heyday of non-cooperation movement was now a mere memory. Trust had given way to distrust. Apart from the riots which periodically disfigured several towns, there was a new bitterness in politics and in the press. There were not a few who put down the new tension to the non-cooperation movement and its alliance with the “Khilafat” cause, and blamed Gandhi for having played with the masses and use them prematurely. “The awakening of the masses,” wrote Gandhi, “was a necessary part of the training. I would do nothing to put the people to sleep again.” However, he wanted this awakening to be diverted into constructive channels. The two communities had to be educated out of the mental morass into which they had slipped. His doctrine of Non-violence held the key not only to the political freedom of the country but also to peace between the communities. Hearts could never be united by breaking heads. A civilized society which had given up violence as a means of settling individual disputes could also eschew violence for reconciling differences between groups. Disagreements could be resolved by mutual tolerance and compromise.

In September 1924, Gandhi went on a twenty-one day fast to ‘purify” himself and “to recover the power to react on the people.” The fast had a soothing effect, but only for a while; India had not yet seen the last of communal wrangles. The problem had really been reduced to the struggle for fruits of political power between the professional classes of the two communities. It was a scramble for crumbs which the British offered to political India. Gandhi had declared that “majorities must set the example of self-sacrifice.” The blank cheque which he later offered to the Muslims was ridiculed by them and resented by the Hindus, but it epitomized his approach to this squabble for seats in legislatures and jobs under the Government. Unfortunately in the course of the negotiations, the Hindus tended to deal with Muslims as the British Government dealt with nationalist India: they made concessions but it was often a case of too little and too late.

During the next three years, while national politics were dominated by communal issues and controversies in legislatures, Gandhi retired from the political scene, to be precise, he retired only from the political controversies of the day to devote his time to the less spectacular but more important task of nation-building “from the bottom up”. He toured the country extensively from one end to the other, using every mode of transport from railway trains to bullock-carts. He exhorted the people to shake off the age-old social evils such as child-marriage and untouchability, and to ply the spinning wheel. Primarily advocated as a solution of the chronic under-employment in the villages, the spinning-wheel in Gandhi’s hands became something more than a simple tool of a cottage industry. In his efforts to “sell” the spinning wheel to the people, he romanticized it. He put it forward not only as a panacea for economic ills but also for national unity and freedom. It became a symbol of defiance of foreign rule; Khadi, the cloth made from yarn spun on the spinning wheel, became the nationalist garment, the ‘livery of freedom’, as Jawaharlal Nehru once picturesquely described it.

By 1929 Indian politics began to recover from the malaise which had affected them after the collapse of the non-cooperation movement seven years before. This recovery was assisted by discontent among industrial workers, peasants and middle class youth. The trade unions became militant bodies. The peasantry was in distress because of an unprecedented economic depression; there was a dramatic no-tax campaign in Bardoli in Gujarat, Gandhi’s home province, under his able lieutenant, Vallabhbhai Patel. The Swaraj Party which had professed an alternative to the Gandhian programme was deeply disillusioned by 1928; dissensions and defections had emasculated it.