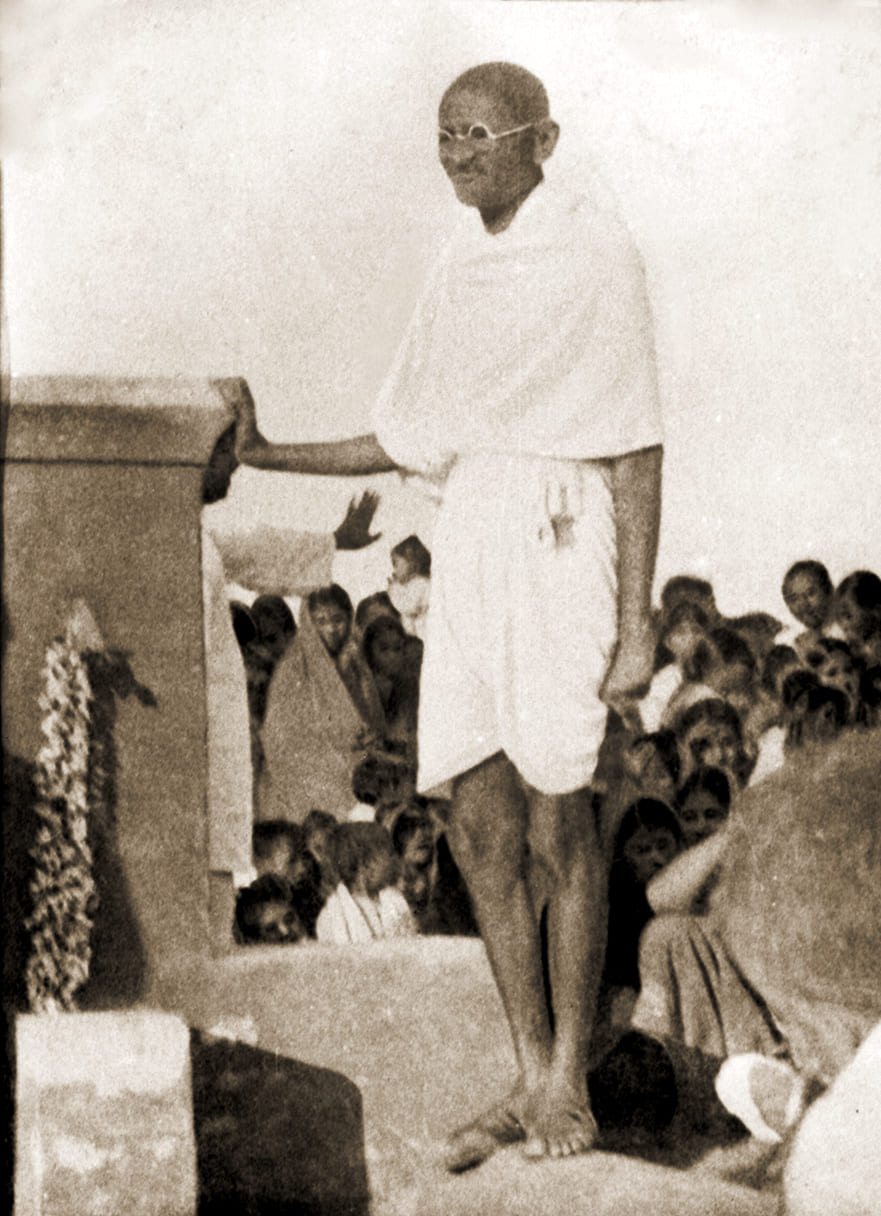

A new twist to the civil disobedience movement came in September 1932 when Gandhi, who was in Yeravada Jail, went on a fast as a protest against the segregation of the so-called “untouchables” in the electoral arrangements planned for the new Indian constitution. Uncharitable critics described the fast as a form of coercion, a political blackmail. Gandhi was aware that his fast did exercise a moral pressure, but the pressure was directed not against those who disagreed with him, but against those who loved him and believed in him. He did not expect his critics to react in the same way as his friends and co-workers, but if his self-crucifixion could demonstrate his sincerity to them, the battle would he more than half-won. He sought to prick the conscience of the people and to convey to them something of his own inner anguish at a monstrous social tyranny. The fast dramatized the issues at stake; ostensibly it suppressed reason, but in fact it was designed to free reason from that mixture of inertia and prejudice which had permitted the evil of untouchability, which condemned millions of Hindus to humiliation, discrimination and hardship.

The news that Gandhi was about to fast shook India from one end to the other. September 20, 1932, when the fast began, was observed as a day of fasting and prayer. At Santiniketan, poet Tagore, dressed in black, spoke to a large gathering on the significance of the fast and the urgency of fighting an age-old evil. There was a spontaneous upsurge of feeling; temples, wells and public places were thrown open to the “untouchables”. A number of Hindu leaders met the representatives of the untouchables; an alternative electoral arrangement was agreed upon, and received the approval of the British Government before Gandhi broke his fast.

More important than the new electoral arrangement was the emotional catharsis through which the Hindu community had passed. The fast was intended by Gandhi “to sting the conscience of the Hindu community into right religious action”. The scrapping of separate electorates was only the beginning of the end of untouchability. Under Gandhi’s inspiration, while he was still in prison, a new organization. Harijan Sevak Sangh was founded to combat untouchability and a new weekly paper, the Harijan, was started. Harijan means “children of God”; it was Gandhi’s name for the “untouchables”.

After his release Gandhi devoted himself almost wholly to the campaign against untouchabilty. On November 7, 1933, he embarked on a country-wide tour which covered 12,500 miles and lasted for nine months. The tour evoked great enthusiasm for the breaking down of the barriers which divided the untouchables from the rest of the Hindu community, but it also provoked the militancy of the orthodox Hindus. On June 25, while Gandhi was on his way to the municipal hall in Poona, a bomb was thrown at his party. Seven persons were injured, but Gandhi was unhurt. He expressed his “deep pity” for the unknown thrower of the bomb. “I am not aching for martyrdom,” he said, “but if it comes in my way in the prosecution of what I consider to be the supreme duty in defence of the faith I hold in common with millions of Hindus, I shall have well earned it.”

Gandhi’s fast had aroused public enthusiasm, but diverted it from political to social issues. In May 1933, he suspended civil disobedience for six weeks. He revived it later, but confined it to himself. A year later he discontinued it; this was a recognition of the fact that the country was fatigued and in no mood to continue a campaign of defiance. These decisions disconcerted many of his adherents, who did not relish his moral and religious approach to political issues, and chafed at his self-imposed restraints. Gandhi sensed the critical mood in the Congress party and in October 1934, announced his retirement from it. For the next three years, not politics but village economics was his dominant interest.

Ever since Gandhi had entered Indian public life in 1915, he had been pleading for a new deal for the village. The acute pressure on land and the absence of supplementary industries had caused chronic unemployment, and under-employment among the peasants whose appalling poverty never ceased to weigh upon Gandhi’s mind. His advocacy of the spinning wheel really derived from its immediate value as a palliative. Since eighty-five per cent of the population of India lived in villages, their economic and social resuscitation seemed to Gandhi to be a sine qua non for freedom from foreign rule. The growing gap in economic standards and social amenities between the village and the town had to be bridged. This could best be done by volunteers from the towns who spread themselves in the countryside to help revive dead or dying village industries, and to improve standards of nutrition, education and sanitation.

It was not Gandhi’s habit to preach what he did not practice; he decided to settle in a village. His choice fell upon Segaon which was situated near Wardha. It had a population of six hundred, and lacked such bare amenities like a pucca road, a shop and a post office. Here, on land owned by his friend and disciple Jamnalal Bajaj, Gandhi occupied a one-room hut. Those who came to see him during the rains had to wade through ankle-deep mud. The climate was inhospitable; there was not an inhabitant of this village who had not

suffered from dysentery or malaria. Gandhi himself fell sick but was resolved not to leave Segaon. He had come alone; he would not allow even his wife to join him. He hoped he would draw his team for village uplift from Segaon itself, but could not prevent his disciples, old and new, from collecting around him. When Dr. John Mott interviewed him in 1937, Gandhi’s

was the solitary hut; before long a colony of mud and bamboo grew up. Among its residents were Prof. Bhansali, who had roamed in forests naked and with sealed lips, subsisting on neem leaves; Maurice Frydman, a Pole, who became a convert to the Gandhian conception of a handicraft civilization based on non-violence; a Sanskrit scholar who was a leper and was housed next to

Gandhi’s hut so that he could tend him; a Japanese monk who (in the words of Mahadev Desai, Gandhi’s Secretary” “worked like a horse and lived like

hermit.”

Sevagram (as Segaon came to be known) was not planned as an ashram. Gandhi never conceived it as such and did not impose any formal discipline upon it. It became a centre of the Gandhian scheme of village welfare. A number of institutions grew up in and around it to take up the various strands of economic and social uplift. The All India Village Industries Association supported and developed such industries as could easily be fostered, required little capital and did not need help from outside the village. The Association set up a school for training village workers and published its own periodical, the Gram Udyog Patrika. There were other organizations such as the Goseva Sangh, which sought to improve the condition and breed of cows and the Hindustani Talimi Sangh, which experimented in Gandhi’s ideas on education.

The educational system in India had always struck Gandhi as inadequate and wasteful. The vast majority of the population could not get the rudiments of education, but even those who went to village primary schools soon unlearnt what was taught to them because it had little to do with their daily lives and environment. Gandhi suggested that elementary education suited to the Indian village could best be imparted through handicrafts so as to substitute a coordinated training in the use of the hand and the eye for a notoriously bookish and volatile learning. .His ideas found an expression in the scheme of “Basic Education” which stirred the stagnant pools of the Indian educational system and stimulated administrators and educationists along new lines.

Work in the village was an arduous and slow affair; it was plodder’s work, as Gandhi once put it. It did not earn banner headlines in the press and did not seem to embarrass the Government. Many of Gandhi’s colleagues did not see how this innocuous activity could help India in advancing to the real goal—that of political freedom. On the other hand, the first official reaction to Gandhi’s village uplift work was to consider it a well-laid plan to spread sedition among the rural masses; the Government of India warned the provincial government to be on their guard and to start counter-propaganda in the village.