Gandhi was thus firmly anchored to pacifism when the war broke out in 1939, but many of his closest colleagues and the rank and file in the Indian National Congress could not bring themselves to accept the feasibility of defending the country against aggression without resort to arms. Twice during the war—after the fall of France in 1940, and the collapse of the British position in South East Asia in 1941—when there was a possibility of a rapprochement between the Congress and the Government for a united war effort, Gandhi stepped aside rather than be a party to organized violence. The rapprochement did not come. The only serious British effort for a compromise was made in the Spring of 1942 with the dispatch of the Cripps Mission to India; that proved abortive.

For nearly two and a half years, Gandhi had resisted pressure from a section of his following for the launching of a mass movement. It became clear that the British Government first under Chamberlain, and then under Churchill, was reluctant to assure Indian freedom in the future, or to offer a practical token of it in the present. Gandhi had endeavoured to restrain the radical wing of the Congress party, and diverted its discontent into “individual Satyagraha”, a subdued form of civil resistance confined to “selected individuals”.

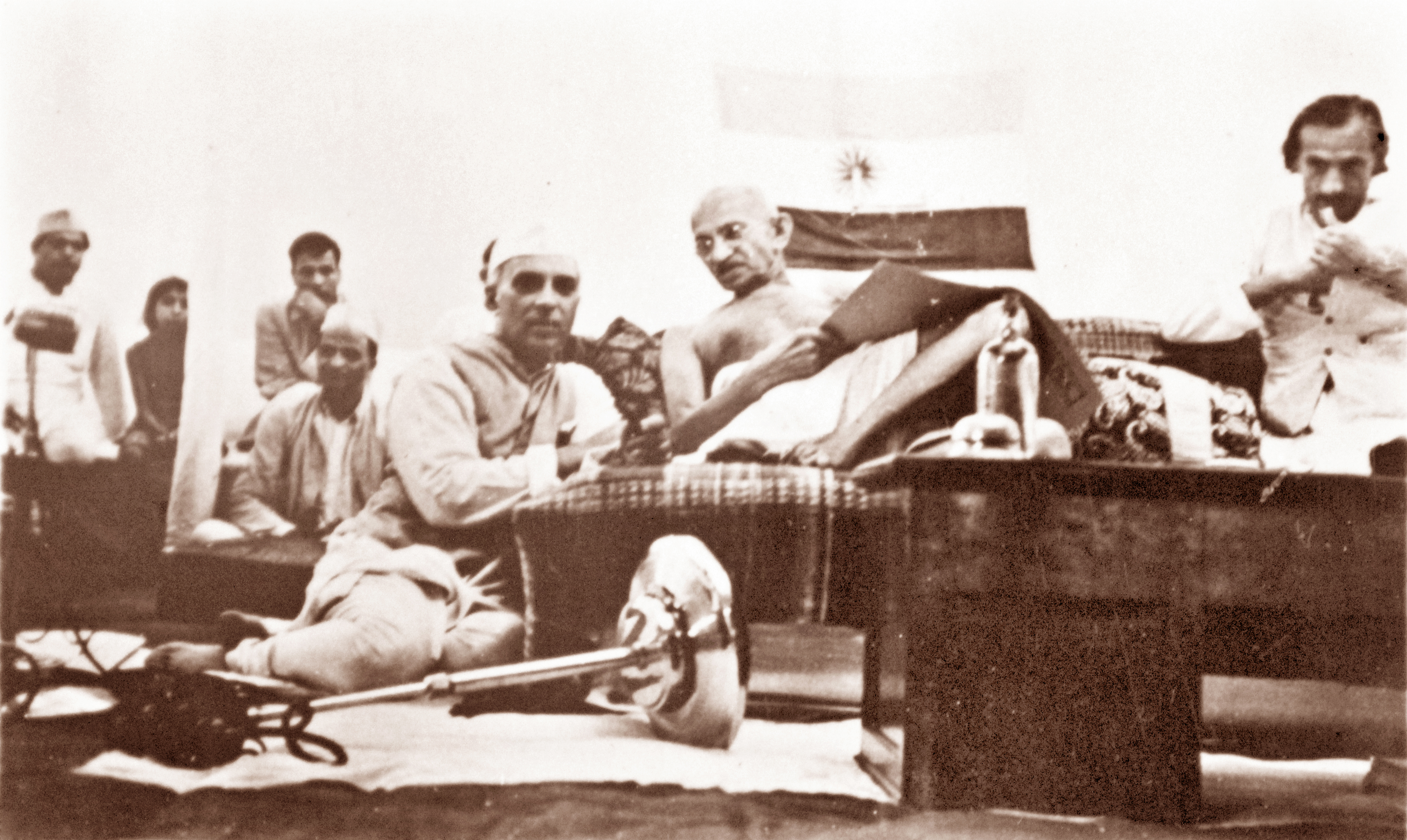

The “Quit India” resolution passed by the All-India Congress Committee brought it into a head-on collision with the Government in August 1942. The Viceroy, with the strong backing of the British Cabinet, struck hard. Gandhi, Nehru and almost all the Congress leaders were imprisoned; the severest repression was launched against the Congress—its funds were frozen, offices sealed and publicity media plugged. The “blitzkrieg” had violent repercussions. In the last speech before the All- India Congress committee before his arrest, Gandhi had made non-violence the basic premise of the struggle which he proposed to launch; this advice remained unheeded between the frenzy of the people and the hammer blows of the Government. In several parts of the country, in Bihar, in U.P., in Bengal and in Bombay, the fury of the people burst the dykes and turned on the instruments and symbols of British rule. “The Congress Party”, Churchill told the House of Commons, “had now abandoned the policy which Mr. Gandhi had so long inculcated in theory and has come into the open as a revolutionary movement.” In India and abroad official propaganda attributed violence to a plot carefully laid by Congress leaders. Gandhi was even accused of being pro-Axis, and assisting a Japanese conquest of India. Official propaganda held the field for a time, but not for long. “It is sheer nonsense.” Smuts, Gandhi’s old antagonist in South Africa, told a press conference in London in November to a columnist “He is a great man. He is one of the great men of the world.”